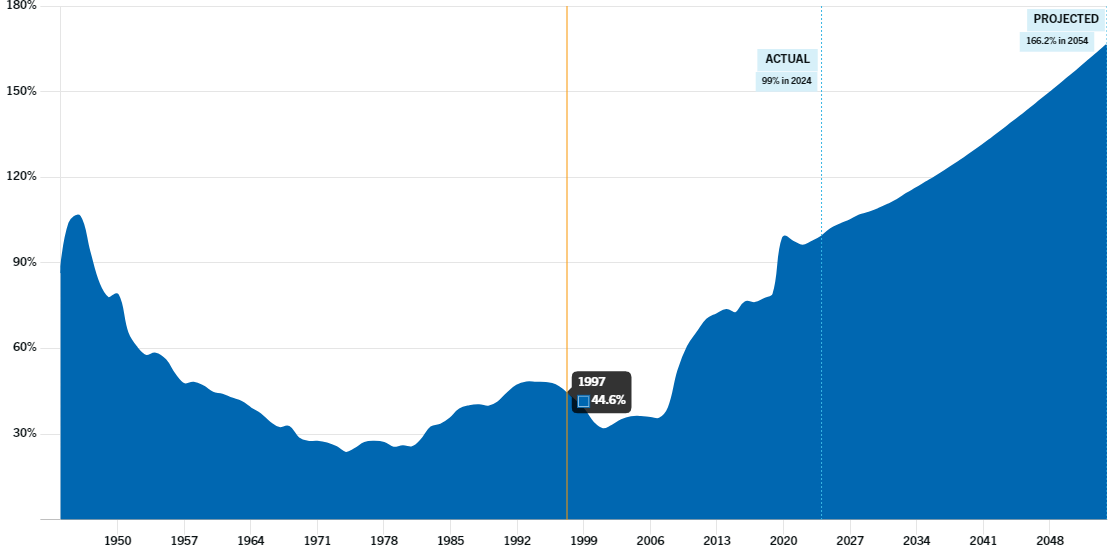

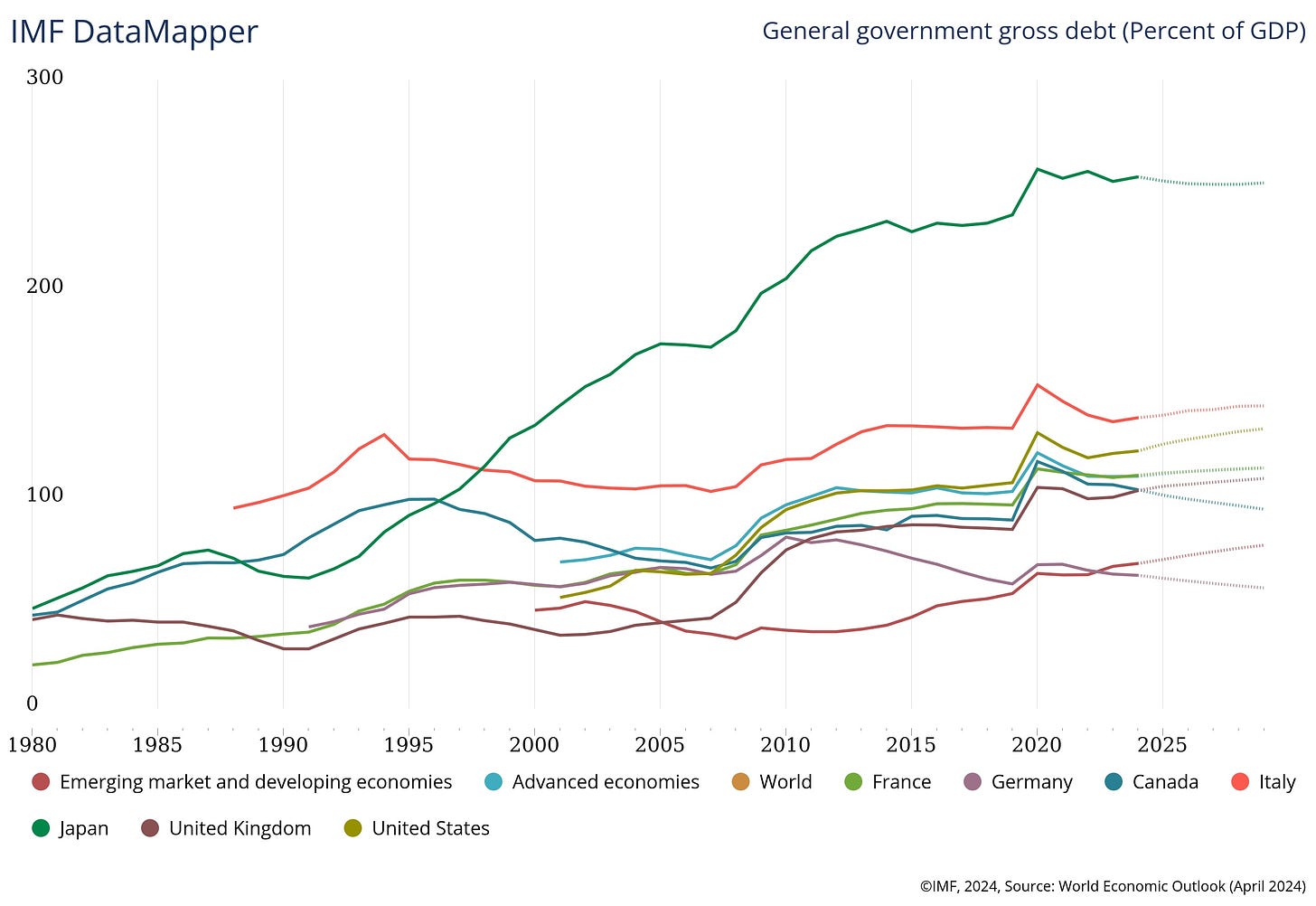

It is becoming clearer that the world is not going to pay back its debt in full. At in excess of $300T, the ratio of global debt to global GDP is over 300%:

What does that mean? Let’s take the US. The US owes $34,594,753,832,437, which represents ~$102,859 per person.

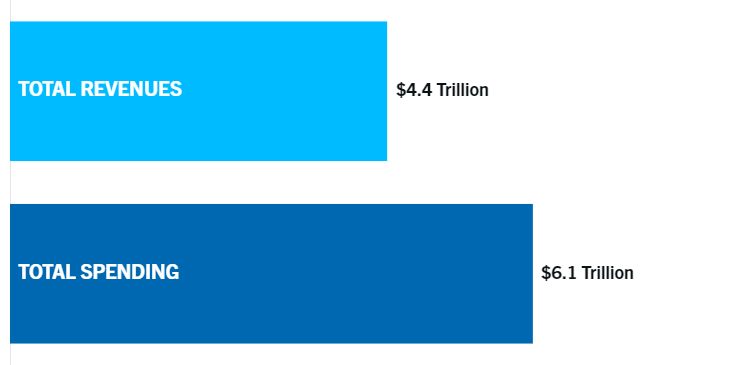

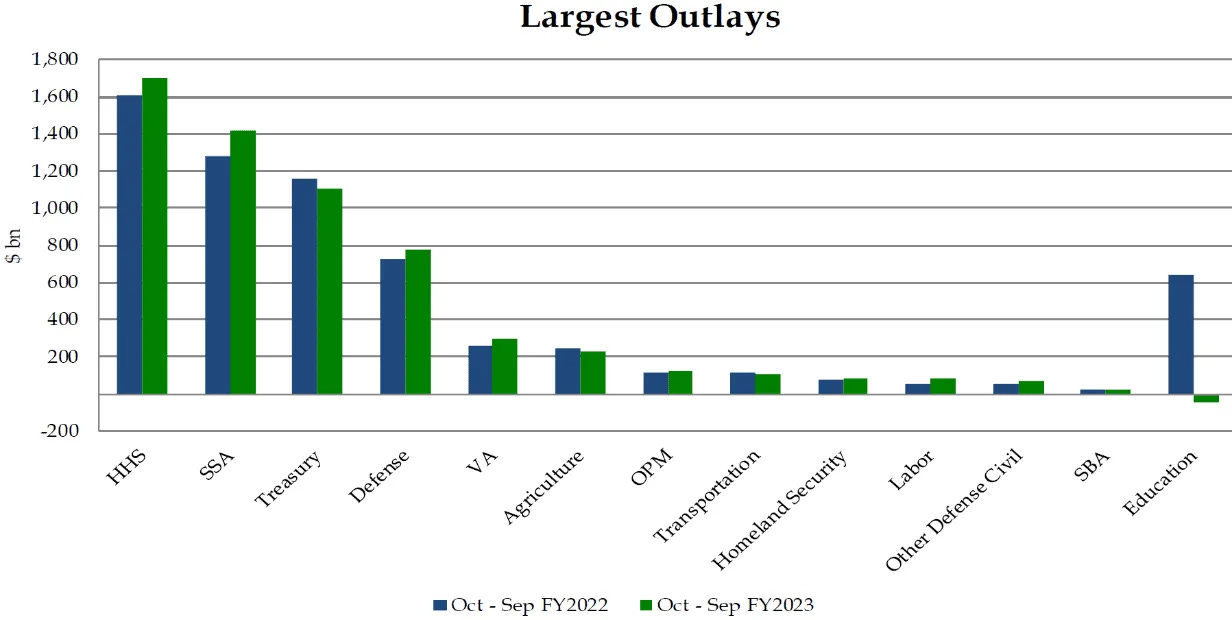

According to the Peterson Foundation (Pete Peterson, one of the founders of the Private Equity firm, Blackstone), we are paying $2.4B of interest every day. That adds up to ~$900B of the ~$2T deficit we are running each year.

2023 Figures were:

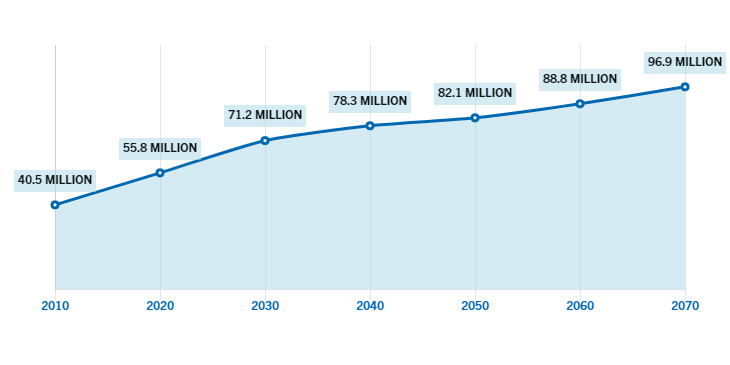

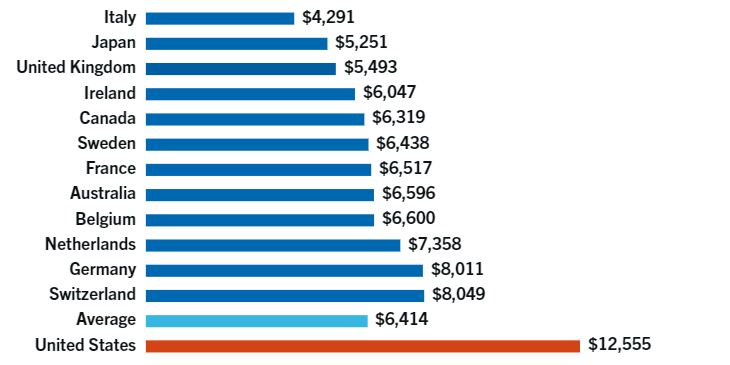

Our demographics are hurting us here because, as a country, we are aging. 10,000 people are turning 65 each day.

As they do so, the burden of healthcare, courtesy of Medicare, transfers to the government. This hurts us because we have easily the highest cost of healthcare in the world (average cost of healthcare per person):

The debt is growing quickly. Everyone's debt is growing quickly. It was fine when interest rates globally were close to zero. Now they are really making an impact at 4-5%. These rates are likely not coming down soon.

So, how does the US set about paying that debt back? I have suggested before that we can inflate our way out of this by growing GDP nominally at a faster rate than the interest on the debt grows. For example, if we continue to grow the deficit at 8% per annum, it will take 9 years to double, unless we cut entitlements and defense spending...which doesn’t seem likely. Entitlements are a huge political hot potato and defense spending...well the post-cold war peace dividend has disappeared quickly.

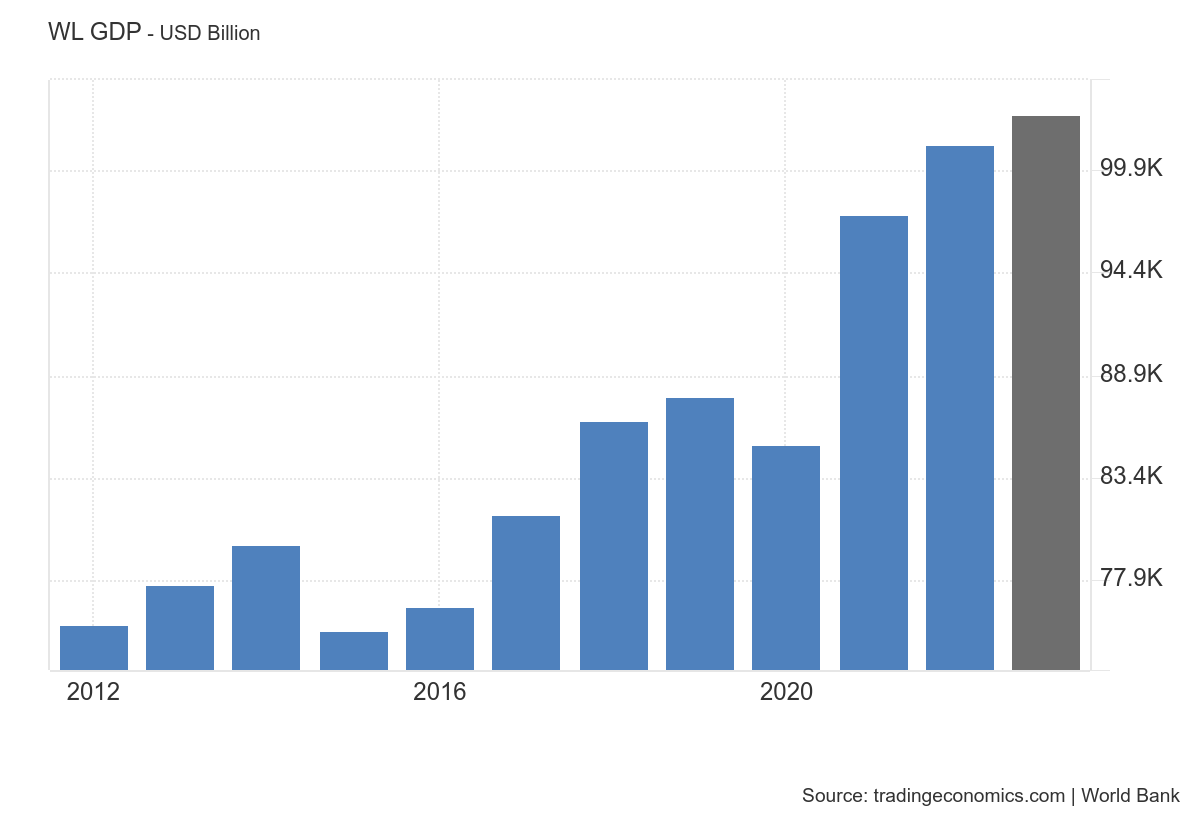

If public debt is $68T in 9 years, GDP would need to be $97T for the ratio to be a more stable 70%. The implied growth rate is just under 15% to get there. Real GDP growth in 2023 was 2.5%. Inflation in 2023 was 3.4%, so overall nominal GDP growth was 5.9%. So, how do we get nominal GDP to grow faster? More inflation.

We can see similar stories in a number of the G7 economies

Getting to 70% debt to GDP, though, is not really about repaying the debt. It is about reducing the debt to a level where the world, the creditors/lenders to the US, believe the burden is manageable.

If the consensus view is that the debt is not going to be repaid, but the lenders believe it can be serviced and rolled over (reissued when due), then everyone is happy: the borrower can continue to pay the interest and extend the debt; the lender continues to earn interest and own a safe asset.

If the debt burden is considered to be too high and interest compared to all the other things the borrower has to pay for is too large, then there is a problem.

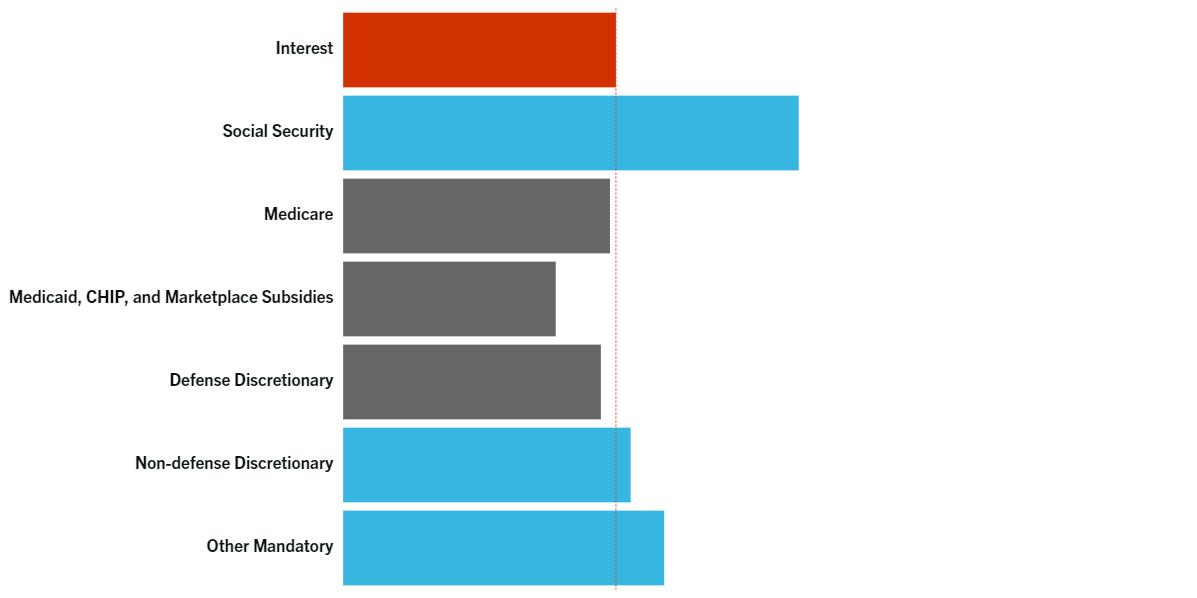

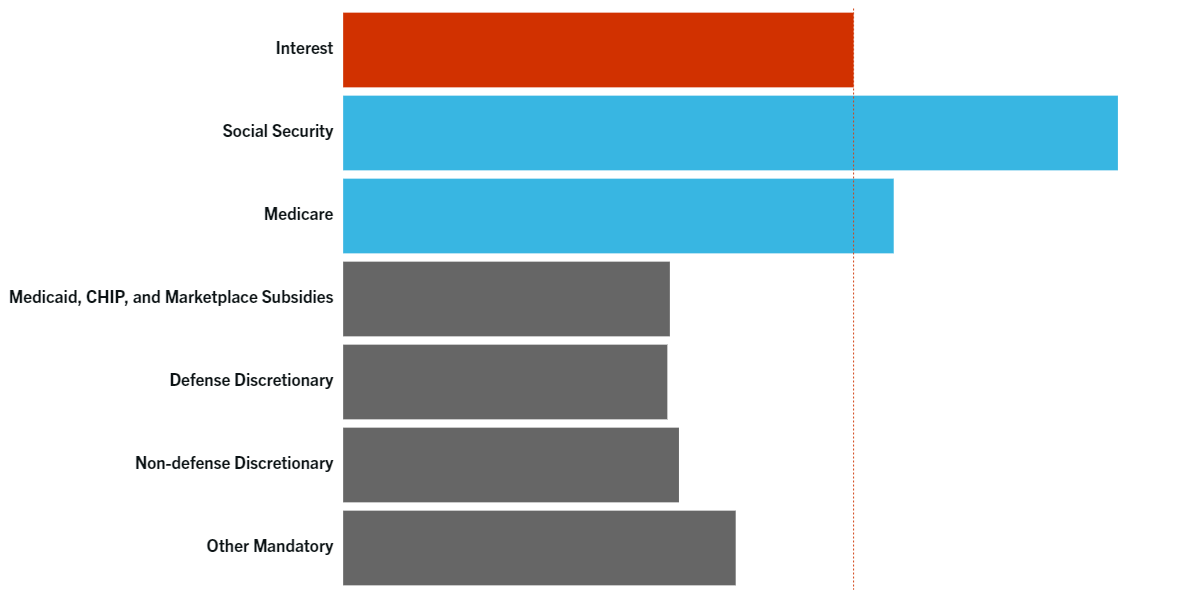

These charts from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) show the current proportion of expenditures and also the projection for 10-years in the future:

2024

2034

Will inflation help? Technically, the idea of inflating our way out of debt is sound. If you own a house, you took out a fixed rate mortgage and you put down, say $100,000 as a 10% down payment on a $1,000,000 home, then you will benefit from inflation, assuming that inflation feeds through to house prices (historically it often has). Assume the price of the home rises by 10% to $1,100,000. Your loan is still $900,000 but your equity is now worth $200,000 - double what you put down.

Renters are not so fortunate. All inflation does for them is to increase their out-of-pocket monthly cost of living, along with the increase in the cost of their monthly food and utility bills. That is the problem with inflation: its benefit is not distributed evenly. Those who own assets already and those with liabilities will benefit from inflation. So, while inflation will tend to help the government restore a more manageable level of debt to GDP, it won’t help those of low to moderate income who don’t own assets.

What if we don’t have inflation to bail out the $300T of global debt? Typically, when debtors can’t pay back their debt, the creditors take control in some way, depending on the terms of the debt and any collateral given as part of the bargain. The borrower has failed to live up to the agreement made to pay interest on the debt and repay it and so has to figure out what next with the lender. The lender will take some or all of the equity of the business and hope to profit from generating revenue without the burden of debt or, if there is no value to the business as a going concern, sell the remaining assets, tangible or intangible, to recoup what they can. The owners will be wiped out.

It’s a bit different with countries because they can’t simply be sold/liquidated. ‘Wiping out’ the owners is tricky: who are the owners? The usual way to handle a sovereign default is to give the lenders, in exchange for their debt forgiveness, valuable, unencumbered assets owned by the public sector/government. There is history from the 80s and 90s of a few different methods of dealing with situations like this: debt restructuring - extending the payback period and lowering the interest rate; debt/equity swaps - where the debt is discharged at a discount in exchange for some ‘stake’ in a valuable national asset - and debt/nature swaps - where the country is forgiven debt in exchange for undertaking some environmental good such as preserving a rain forest.

All these techniques have flaws and views are mixed as to how effective they are. The most effective solution may be for the lenders to take a write-off, accept the pain and move on to fight another economic cycle. If a country has borrowed in its own currency, then the easiest way is usually to print money to pay or roll over the debt -expanding the money supply. Usually, this is inflationary because it creates more money chasing the same amount of goods and services. If the sovereign country happens to have borrowed in another currency - USD for example, a pretty common occurrence - then they can’t print their way out of the debt burden.

The US, of course, has nearly always borrowed in USD and, so far has been able to and for the foreseeable future probably will be able to issue more debt to refinance its existing debt...until it can’t. The poster child here is Japan, whose debt to GDP ratio (see chart above) exceeds 250%. Netting off the ~47% of Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) that the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has bought, that figure is closer to 143%. Important to note that the US has some similar options available to it: the Federal Reserve has, through something called quantitative easing, bought nearly $8T of Treasury Bonds and Mortgage Backed Securities.

“Printing money” comes in a few different varieties - a topic for another day...but, for those keen to dig deeper, take a look at www.fiscaldata.treasury.gov. One of the many things the US has going for it is the transparency of the data it presents about its own finances. Not always pretty, but there for inquiring eyes...